100x speedup on Python with just a touch of C++

Python is a great language. I still remember my first contact with Python2 some 8 years ago, and I was amazed by how clean and expressive it was. And now, with Python3, a lot has changed. It is now the de facto language for machine learning (so long, Matlab!), and lots of amazing stuff have been built with it.

All is good and dandy, however from time to time I’ve encountered a brick wall when working on Python: how slow it is. Don’t get me wrong, if you are using libs to do your heavy processing, such as NumPy, you are good to go. But it’s important to notice that the core of NumPy is not Python, and for a reason. It’s just not the language for that.

For most cases, you can use such libs and pass those crunch-intensive stuff to them, but sometimes you want something not so conventional and that does not conform with such limitations. And then you end up writing two nested fors in Python, processing a Full HD image, and you want to cry…

Fortunately, we can write those code hot spots in C++, and it is surprisingly simple to do it and seamlessly integrate with Python. However, this opens another can of worms that is C++, and its dependencies and compatibilities. For anyone that had to target Linux, Windows in both 32 and 64 bits should know what I’m talking about. So for me it is of the utmost importance that it can be used seamlessly in any platform without any dependencies other than a C++ compiler.

So upfront I’m already discarding Boost.Python and PyBind11. I’ve used both, and usually prefer PyBind11 since it is much easier to manage on different platforms. But one dependency is one too many. And as I will show it now, you don’t need them for most cases.

Let’s start with a very simple and naive example: normalize the contrast of a black and white image.

import numpy as np

def naive_contrast_image(image):

result = np.zeros(image.shape, dtype=np.uint8)

min_color, max_color = np.min(image), np.max(image)

delta_color = max_color-min_color

for row in range(image.shape[0]):

for col in range(image.shape[1]):

pixel = image[row,col]

result[row,col] = 255*(pixel-min_color)/delta_color

return result

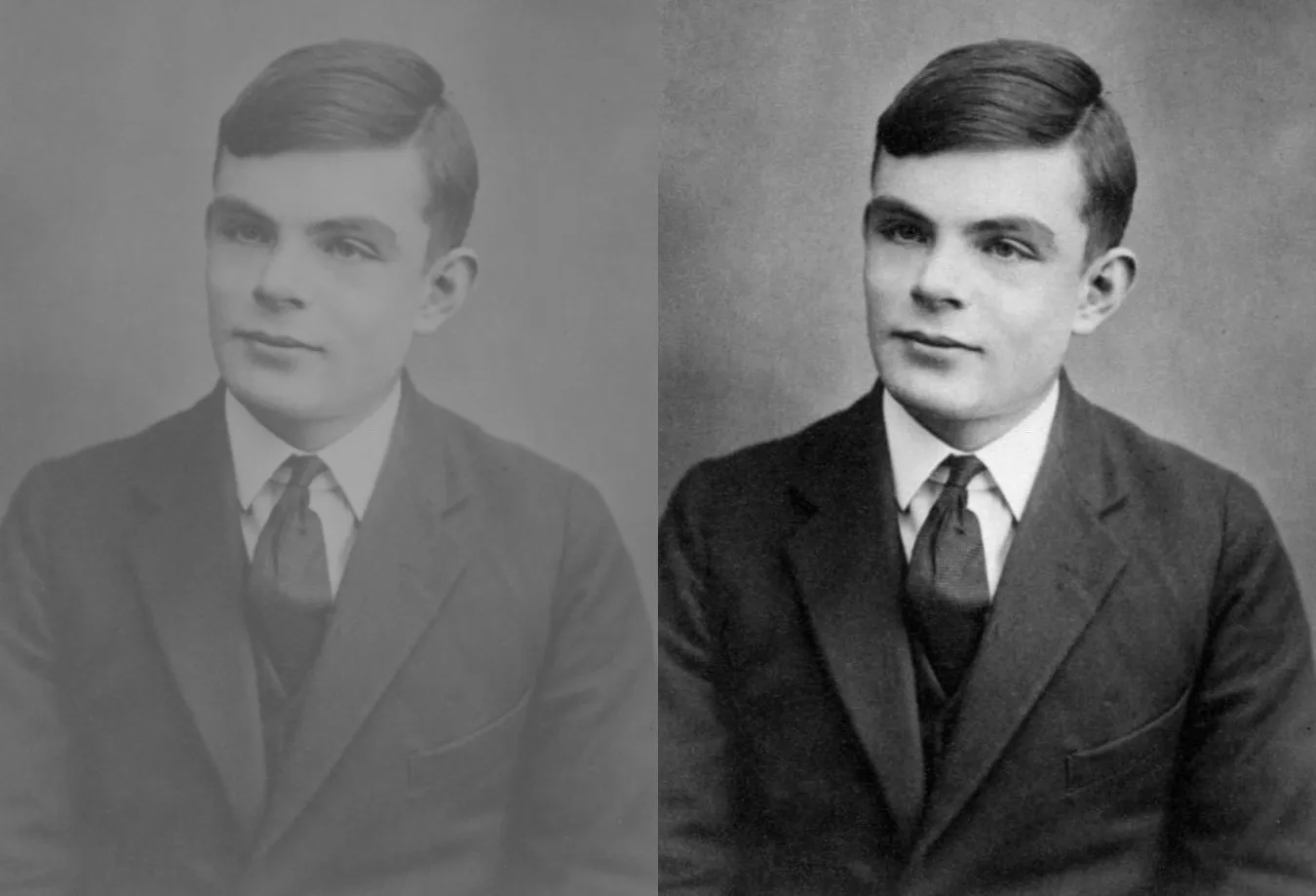

So this code generates the following result:

This is a very simple and naive example that could (and should) be done using NumPy. But let us do this in C++.

The first difference in C++ is that you should specify the variable types. So let us define image as an np.uint8 array, and the resulting image with the same type. On C++ this can be represented as unsigned char. Let’s take a look at our implementation. On contrast_image.h:

#include <algorithm>

#include <vector>

extern "C" {

void cpp_contrast_image(const unsigned char *image, int height, int width, unsigned char *outResult);

} // extern "C"

And contrast_image.cpp:

#include "contrast_image.h"

void cpp_contrast_image(const unsigned char *image, int height, int width, unsigned char *outResult) {

auto vec = std::vector<unsigned char>(image, image+width*height);

auto minmax = std::minmax_element(vec.begin(), vec.end());

float min = (float)*minmax.first;

float max = (float)*minmax.second;

float delta_color = max-min;

for (int row=0; row<height; row++) {

for (int col=0; col<width; col++) {

int idx = row*width + col;

float pixel = (float)image[idx];

outResult[idx] = (unsigned char)(255*(pixel-min)/delta_color);

}

}

}

There are some small but very important details here, so let’s start with the important ones.

- Avoid dynamic memory allocation on C++. Python Garbage Collector will not see them so you will have to free them by yourself. Prefer to allocate the memory with NumPy. This will be shown further along.

- Multiple dimensional arrays are actually just a single array with some syntactic sugar to access it. You’ll notice the direct idx calculation on the example. It is a good practice to create a function to give you the index given the desired position to avoid silly bugs.

- Access and/or modify an invalid array position will generate the dreadful Segmentation Fault. So always be diligent with the range checks.

- The function must have a C compatible interface, as we can see with the extern “C” on contrast_image.h. Usually this is not a big deal since we can use all the desired C++ stuff within the implementation on contrast_image.cpp, however we will have to implement different versions for different input types since templates are not available on the function definition :(.

Finally, returning complex objects within a C interface is not the easiest and cleanest thing to do. So for the most part I just reserve my final arguments to return my value. And also, use const on every array that you should not change and let the compiler help you find bugs.

Ok, we have a C++ code that does exactly what we want and can compile it to a lib with:

g++ -Wall -O2 -c -fPIC contrast_image.cpp

g++ contrast_image.o -shared -o libcontrast_image.so

Until now I did not say anything out of the ordinary, but we are surprisingly close to finishing it. Python has a useful and easy way to access a C compiled libs using ctypes. So this is how we will use our cpp_contrast_image on Python:

import ctypes

import numpy as np

from numpy.ctypeslib import ndpointer

lib = ctypes.CDLL('./libcontrast_image.so')

c_contrast_image = lib.cpp_contrast_image

c_contrast_image.argtypes = [

ndpointer(ctypes.c_ubyte, flags='C_CONTIGUOUS'),

ctypes.c_int,

ctypes.c_int,

ndpointer(ctypes.c_ubyte, flags='C_CONTIGUOUS'),

]

def contrast_image(image):

result = np.zeros(image.shape, dtype=np.uint8)

c_contrast_image(image, image.shape[0], image.shape[1], result)

return result

And that’s it! You can use the new contrast_image python function with exactly the same interface, but much faster! How fast, you may ask. Well, on my i7 8550-U it went from 1229.050ms to 1.645ms on this demo image. Quite a difference! That’s actually over 700x faster, way over the promised 100x. The reason is that in our use cases we often see a speedup of a little over 100 times, so I’m trying to not over-promise here.

Just as with our C++ code, we have some important stuff to notice here. So let’s do it:

- On C++ we treated our NumPy arrays as a single contiguous array. Usually that is the case, but not always! Fortunately we can explicit this constraint on Python itself, informing that our NumPy array is of type char and must be contiguous. If you call it with the wrong type an exception will be raised, saving you from a possible Segmentation Fault. You can check the available c_types here.

- Remember that we are avoiding to allocate memory on the C++ code? So we are doing it here, by explicitly allocating the result image with np.zeros.

- We have to explicitly point to where our compiled C++ library is to be loaded from, using ctypes.CDLL.

That’s it! Within a few lines of code you have lots of freedom to easily integrate C++ code into Python, and all of that without any dependency :)

You may be thinking that this is a silly example. And you are right. But you can do lots of stuff with this knowledge. For example, we decreased the runtime of a rasterization algorithm from 2.5s to 1.8ms, quite a hefty difference! You can read all of that on a following post to be released. But I’ll warn you, it was really easy :)

Finally, I must quote a great thinker: “With great powers comes great responsibility”. For an untrained person dabbling with pointers at C++ is a quick road to memory leaks and Segmentation Faults. Actually, even for trained ones. So it is a good practice to keep those codes as short as possible, usually not replacing a whole function but just the slow parts. And don’t forget to do lots of unit tests to catch some unusual edge cases. But if you are willing to deal with those drawbacks, a whole new world of crazy fast code awaits you!

PS.: All of this code and the benchmark script can be seen on https://github.com/gfickel/python_cpp. It is meant to only illustrate the interface between C++ and Python, so everything surrounding it is not production ready. This is up to the reader ;)

PS2.: Thanks to Michele Tanus, Gustavo Führ and Roger Granada for proofreading and greatly improving this post.