Creating a Model Server and Making Better Wheels

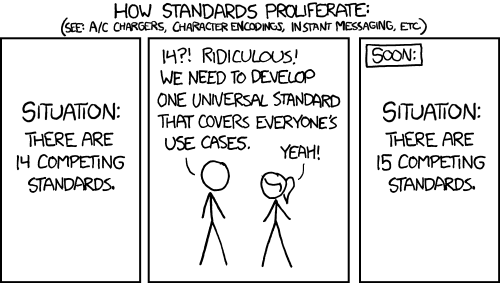

There are already some pretty good model servers with really good features, like Triton, TorchServer and TensorFlow Serving. So… why make another one when xkcd already warned us?

I took some liberties using this comic strip, but the main point remains: why try to reinvent the wheel? This is an old and trusty saying, and there is so much new stuff that we could be creating instead of redoing something that has been done by several people, often with more experience in this particular area than you. But I don’t fully buy into that. It is a good rule of thumb for the, probably, vast majority of time, but not always. As John Carmack said in his Commencement Speech at UMKC: “It’s almost perceived wisdom that you shouldn’t reinvent the wheel, but I urge you to occasionally try anyway. You’ll be better for the effort, and this is how we eventually end up with better wheels.” Getting better wheels is hard and not always guaranteed, but getting better for the effort is always the case.

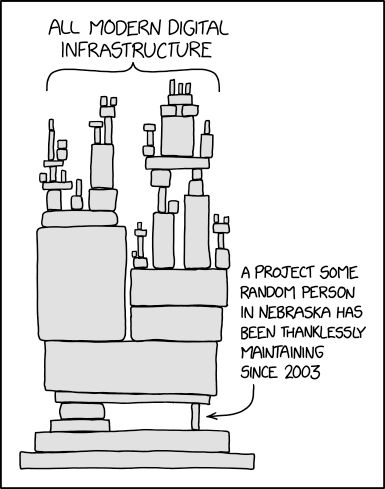

So getting back to our Model Server project, I wanted something that was simple to use and could add any model that I wanted, either PyTorch, TensorFlow, or ONNX, using both CPU and GPU. Also, there is the hidden cost of using a big Open Source project that is fixing and debugging code. Don’t get me wrong, Open Source is awesome, but to immerse yourself into lots of new code, with several layers of little (and often not) documented abstractions is no easy feat. And like the following wisdom of xkcd warned us, we really should be careful when depending on a large stack of dependencies that we can barely grasp.

I will be starting with Python, since it is the language most used by ML folks, and should make our life easier when importing some more obscure and heavily code-dependent models. And to do our server gRPC seems like a great call: it is supported in a bunch of languages and defines the server interfaces through protobufs, which I quite like since it makes way harder to commit some silly errors passing and getting data from it. Let’s build it in parts, starting as simple as possible and adding new features after. If you want to look at the final code, check it out here: https://github.com/gfickel/tiny_model_server

Barebones Server

With those previous definitions in mind, we can almost start writing the skeleton of a server, we just need to figure out how to define our interface and write the appropriate protobuf. Since I mostly deal with images, I’ll start implementing a route to receive an image and return a dict with the results. Let’s start with the protobuf:

syntax = "proto3";

service Server {

RPC RunImage(ImageArgs) returns (Response) {}

}

message ImageArgs {

NumpyImage image = 1;

string model = 2;

}

message Response {

string data = 1;

}

There is a lot to unpack here. You can check the Protobuf Docs for more details, but the main point here is the declaration of a service Server that has an RPC called RunImage. This RPC takes an ImageArgs and returns a Response. Looking at a high level all seems to make sense, so let’s look a little bit closer.

ImageArgs and Response are both messages, that define how to pass and get data around to our server. Response has only a single field called data of type string. So we are getting a string back from our server after we call ImageArgs. It is not the dictionary we wanted, but we can easily encode and decode to string using json lib. Regarding ImageArgs, things get a little bit more complicated: we have a NumpyImage image that is the binary data and a string that defines what model we want. The most tricky part is the NumpyImage part, and that’s how I defined it:

message NumpyImage {

int32 height = 1;

int32 width = 2;

int32 channels = 3;

bytes data = 4;

string dtype = 5;

}

We have the height, width, and number of channels as integer types, the numpy dtype stored as a string, and the binary data on data. With all of this, we can almost send and receive numpy images (matrices) at will, we just need 2 things: learn how to access those datatypes in our Python and write some code to help us encode and decode to this format. To solve the first problem we must “compile” our protobuf file that will generate some Python code that we’ll use. Here’s the command:

python -m grpc_tools.protoc -I. --python_out=./ --pyi_out=./ --grpc_python_out=./ simple_server.proto

This command will read our protobuf file and generate two new python files: simple_server_pb2.py and simple_server_pb2_grpc.py. I’ll mention them when we use them, but the main point is that they provide interfaces to our protobuf definitions.

And now, on the code to encode and decode our numpy images to the Protobuf messages:

np_dtype_to_str = {

np.dtype(np.uint8) : 'uint8',

np.dtype(np.float32) : 'float32',

np.dtype(np.float64) : 'float64',

}

str_to_np_dtype = {v: k for k,v in np_dtype_to_str.items()}

def numpy_to_proto(mat):

dtype_str = np_dtype_to_str[mat.dtype]

return simple_server_pb2.NumpyImage(

height=mat.shape[0],

width=mat.shape[1],

channels=(1 if len(mat.shape)==2 else mat.shape[2]),

data=mat.tobytes(),

dtype=dtype_str

)

def proto_to_numpy(image):

dtype = str_to_np_dtype[image.dtype]

np_image = np.frombuffer(image.data, dtype=dtype)

if image.channels == 1:

shape = (image.height, image.width)

else:

shape = (image.height, image.width, image.channels)

return np_image.reshape(shape)

It is a quite straightforward code, with two different functions: one to encode a numpy image to a protobuf message, and another to do the opposite. I’ve hardcoded the supported dtypes on np_dtype_to_str, but it is trivial to expand to other ones. You may notice that we are using simple_server_pb2 here, and that’s one of the automatically generated Python codes that I’ve mentioned. Ok, finally we have defined our interface and created our protobuf accordingly, we are just missing the most important part: the server! And here we have it:

class SimpleServer(simple_server_pb2_grpc.SimpleServer):

def __init__(self):

self.models = {}

def RunImage(self, request, context):

model_name = request.model

image = proto_to_numpy(request.image)

# results = self.models[model_name).run(image)

results = {'score': 42.0}

return simple_server_pb2.Response(

data=json.dumps(results))

def serve():

server = grpc.server(

futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=8))

route_servicer = SimpleServer()

server_pb2_grpc.add_SimpleServerServicer_to_server(

route_servicer, server)

server.add_insecure_port('[::]:50051')

server.start()

server.wait_for_termination()

if __name__ == '__main__':

serve()

Ok, now we have finally a server running! But first, let’s look at this code and see how it is done. First, we defined a class called SimpleServer that inherits another SimpleServer from simple_server_pb2_grpc, the other one of those automatically generated codes from protobuf. It provides all the nitty gritty stuff to create a gRPC service, and we just need to define our RPC routes as methods. In our case, that is RunImage, which gets an ImageArgs message, decodes our image back to numpy with proto_to_numpy, and gets the desired model from request.model, calls it and return a Response message. You may notice that we are faking running a model and returning a fixed response. This is the subject of our next Section.

With this SimpleServer in hand, we just need to set up a gRPC server and run it. There is not much going on there, we are basically creating a server with max_worker threads, adding our SimpleServer service to this server, defining a port to run it, and starting it. You can check out this official tutorial to get some more insights, but we’ll get back to those in future sections.

Adding Models

Ok, we have a model server that it is doing “everything”, except run models. Let’s tackle that. Recording one of our goals: it must be easy to add new models, even if they contain lots of Python code. I believe that one of the easiest things would be to create a defined interface that each model must comply with, and our model server loads all of them. For instance, we can have this base interface as the following:

class ModelInterface(abc.ABC):

def get_input_shape(self):

""" Returns numpy shape """

return None

@abc.abstractmethod

def run(self, data, args):

""" Returns a response dict """

def run_batch(self, data, args):

""" Same interface as run, however, the images batch is encoded on

a single numpy image. If the model does not provide a batch option

just call it once for every input data.

"""

return [self.run(x, args) for x in data]

And our model code would be something like this:

class Model(ModelInterface):

def __init__(self):

""" Here you may load an instance of your model """

self.model = 'load my model here'

def get_input_shape(self):

""" Returns just like numpy shape """

return (1080, 1920, 3)

def run(self, data, args):

return [('object1',0.3),('object2',0.5)]

The idea is to inherent ModelInterface, load our model on __init__, and define, at least, the method run. Since all of this is just plain Python, we can do everything we want within run, which should make it quite simple to add here. For example, I’ve already used [MTCNN][https://github.com/davidsandberg/facenet/tree/master/src/align] which has quite a lot of Python code to deal with 3 different Neural Networks used in a cascade fashion, and it was straightforward to add it here.

Now the only problem left is to make our server find those models. I’m using a simple solution, consisting of creating a new folder within models/ with the name of your model, and inside it, you will have an __init__.py with this class Model that implements the run method, and you can put whatever extra necessary code in there. Inside our server we can check all the available models like this:

all_models = os.listdir('models/')

The last piece of the puzzle is to actually import and instantiate those models to a usable Python object. You can do this with https://docs.python.org/3/library/importlib.html, which enables us to import a module whose path is decided at runtime. In the end, we can have something like this on our server:

for model in os.listdir('models/'):

model_path = f'models.{model}'

module = __import__(model_path, globals(), locals(), ['object'])

importlib.reload(module)

self.models[model) = module.Model()

With this code, we are instantiating all of our models and putting them into a dict, with its name as key. So, we can update our server code to be like this:

class SimpleServer(simple_server_pb2_grpc.SimpleServer):

def __init__(self):

for model in os.listdir('models/'):

model_path = f'models.{model}'

module = __import__(model_path, globals(), locals(), ['object'])

importlib.reload(module)

self.models[model) = module.Model()

def RunImage(self, request, context):

model_name = request.model

image = proto_to_numpy(request.image)

results = self.models[model_name).run(image)

return simple_server_pb2.Response(

data=json.dumps(results))

def serve():

server = grpc.server(

futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=8))

route_servicer = SimpleServer()

server_pb2_grpc.add_SimpleServerServicer_to_server(

route_servicer, server)

server.add_insecure_port('[::]:50051')

server.start()

server.wait_for_termination()

if __name__ == '__main__':

serve()

Finally, we have a working model server! But wait, how do I call it? I can add as many models as I want, but how do I actually use this in my code? That’s a question for the next Section.

Calling Model Server

We have a fully functional model server, but all will be in vain if it is a pain to use. Fortunately, we can make things easier by creating a Model Client, that your code can use. Ideally, we want to establish a client for each model within a single line, and another one to run the model. It really should be that simple, and the complexity should be invisible to the user. A good practice when defining interfaces is to write the final code how you think it should behave, with all (and only) information necessary. This is our end goal:

model = ModelClient(model='example_image', ip='localhost', port=50000)

res = mode.run_image(image)

I’ve mentioned hiding the complexity but really there is not much to it. Mostly is just making sure that we managed to connect to our server and some boilerplate code to convert data back and forward. Let’s look at what it looks like:

class ModelClient(abc.ABC):

def __init__(self, model: str, ip: str, port: str='50000', timeout: int=60*5):

self.model = model

self.channel = None

self.stub = None

self.size = None

self._connect(ip, port, timeout)

def _connect(self, ip: str, port: str, timeout: int):

channel = grpc.insecure_channel(f'{ip}:{port}')

self.stub = server_pb2_grpc.ServerStub(channel)

begin = time.time()

while self.size is None: # keep trying to connect until timeout

try:

response = stub.GetInputSize(

server_pb2.StringArg(data=self.model))

self.size = json.loads(response.data)

except grpc._channel._InactiveRpcError:

time.sleep(1)

if time.time()-begin > timeout and self.size is None:

raise ConnectionTimeout(ip, port, timeout)

def _get_image_arg(self, image: np.array):

image_proto = utils.numpy_to_proto(image)

return server_pb2.ImageArgs(

image=image_proto,

model=self.model)

def run_image(self, image: np.array):

"""Runs an image into the given model."""

if image is None or min(image.shape[0:2]) <= 2:

return {'error': 'Bad image'}

run_arg = self._get_image_arg(image)

response = self.stub.RunImage(run_arg)

return json.loads(response.data)

That’s a lot of code, so let’s start at the beginning. Our ModelClient takes as a parameter the model name (defined by its folder name), the ip and port of the server, and a connection timeout. On __init__ we just call _connect which creates a channel and a stub to the server. The idea here is to have a single channel and stub per model that we always keep open, so on every new model call we don’t have to deal with all the handshaking stuff.

Notice that on _connect we keep trying to call GetInputShape RPC in order to see if our model server is on and responding. It is quite common to launch the model server at the same time as the application, and the model server may take longer to be up and running, so it is good to have a timeout to keep trying for a little bit. After we get our model input shape we are done and ready.

To use our client we are going to call the run_image method, which takes an image and returns a dict. We are using a helper method called _get_image_arg to format our ImageArgs protobuf message, and calling our server through our stub. Finally, we are getting the results from .data, which is a string, and converting it back to a dict with json.loads.

And that’s it, quite easy for our end user. Notice that despite ModelClient hiding most of the complexities, it is still quite in reach for any user to debug its code and make changes as they see fit. Talking about changes… what about performance?

Multiprocessing Server

Yeah, performance is key, and a simple and easy to use model server is quite limited if we can’t scale vertically on this day and age of multiple GPUs and many cores CPUs. This is super simple on other servers, like gunicorn, but things are more barebones with gRPC. We have the max_workers argument when creating a server, but those workers are threads, and in python, they do not execute parallel code. They are great when there are many stalls due to IO, for example, but they don’t help us using our several CPU cores for max performance.

Reading gRPC’s own multiprocessing example, we have to do some tricks:

- Fork our server code at the right time to create multiple processes

- Create a connection with the option so_reuseport. This makes it possible for all of our forks to share the same port, and the Unix kernel will be responsible for doing the load balancing

- This kernel load balancing doesn’t work if we want to keep our connection open to the server, since it will always be calling the same exact worker. We have to do load balancing manually

First, let’s create those several process parallel workers. We can do this by changing our server code a little bit:

def _run_server(bind_address):

"""Starts a server in a subprocess."""

options = (('grpc.so_reuseport', 1),)

server = grpc.server(

ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=8,),

options=options)

server_pb2_grpc.add_ServerServicer_to_server(ServerServicer(), server)

server.add_insecure_port(bind_address)

server.start()

server.wait_for_termination()

@contextlib.contextmanager

def _reserve_port(port_number):

"""Find and reserve a port for all subprocesses to use."""

sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET6, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

sock.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEPORT, 1)

sock.bind(('', port_number))

yield sock.getsockname()[1]

def main():

with _reserve_port(PORT_NUMBER) as port:

bind_address = f'[::]:{port}'

with Pool(processes=NUM_PARALLEL_WORKERS) as pool:

pool.starmap(_run_server, [(bind_address,) for _ in range(NUM_PARALLEL_WORKERS)])

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Quite a little bit more code, so let’s dig in. First, we are calling _reserve_port with our port number. This function uses the socket library to bind to our desired port and set the SO_REUSEPORT flag so that we can fork our server and share the same port. Then we are using multiprocessing.Pool with our _run_server function that actually runs the server. This code is very similar to the old one, but now we are passing grpc.so_reuseport option to our grpc.server. That’s it, we now have a gRPC server that is running on NUM_PARALLEL_WORKERS workers in a truly parallel fashion.

The final piece of the puzzle here is the load balancer part. As previously mentioned, with this multiprocessing approach, it is up to the Unix kernel to distribute incoming connections to all available workers, however, this is a non-stopper for our use case. It is way too expensive to open and close a new connection for every model call. How can we solve this?

Well, the simplest but still pretty good solution that I’ve found is to implement a route on a server that will return the number of parallel workers that it has and the current worker PID (process ID). On the client side, I’ll keep opening several connections until I’ve established at least one on each server, so the client can freely choose where to send. This means that all the load balancing is going to be on the client side… Couldn’t we do this on the server side for maximum performance?

We could, but it requires a third piece on our puzzle, that will receive all the client’s requests and call the appropriate worker. The good thing is that this middleware sees all the clients and how each server worker is operating, so it has all the information to make the best decisions. However, this solution has two major drawbacks: adds another cost of transferring data, we’ll have client->middleware->server instead of client->server, and adds another layer of complexity. Those reasons are enough for me to choose client-side load balancing, and for my use, it is good enough.

There are many options to do client-side load balancing, but let’s start with the simplest: Round Robing. Basically, for a set of N workers, first, we’ll call Worker 1, then Worker 2, and thereafter, always make sure that we are spreading the load across all workers within time. That is how I implemented it, took only one line of code and it is working great! But this is an area where we could definitely improve: choose randomly the next worker so that we are less likely to have multiple clients in sync and stressing the same workers in the same order, or perhaps get some worker usage response attached to each RPC so we could do some more clever thinking before choosing. But for now, it is good enough.

Final Version and Next Steps

Our final code is a little bit more feature complete: it has unit tests, builds a Docker image that makes it easy to use with Kubernetes for scaling it horizontally, and more interface options and error checks. You can check here.

But there are many things missing, including but not limited to:

- Route to process an image and return an image. Useful for image segmentation, optical flow (returning a HxWx2 np.float32 image, most likely), and other applications. I already added ImageResponse as a message on server.proto, I just need to implement a new route.

- Better client-side load balancing as we mentioned.

- Some Kubernetes configs for easy horizontal scaling.

- Add some configurations to environment variables, such as port number and number of parallel workers. They can be easily when running the Docker images.

- Add Locust load tests.

- Add support to ssl_server_credentials.

The good thing about being so small is that those things are somewhat simple to implement. And by simple I mean that there is not a lot of moving pieces here to keep track of, and they could be accomplished with a few lines of code.

Conclusion

That was a journey, but we managed to have a fully working Model Server with only 483 total lines of Python code! And that is including comments and empty lines (although I’m excluding the unit tests and example models). And if we look at our requirements.txt we have only gRPC related packages, numpy and Pillow to deal with images, and pytest for our testing purposes. That seems like a reasonable list.

In the end, I expect that the main takeaway point here is not a tutorial on “How to Create an Awesome Model Server with only 400 lines of code!!!!”, but to be an inspiration to let us explore new avenues, learn more about surrounding topics, and in the process becoming a better programmer. This experience definitely changed the way I see and judge other model servers for my projects, both for “good” and “bad”. The “bad” is that I know how simple things can be, and sometimes drives me nuts having to deal with dependencies conflicts and tons of documentation just to add my model and start testing. On the other hand, there are also the “good” parts. I do appreciate even more all the features that may sound trivial but make our lives so much easier and can be a pain to implement.

Making better wheels is definitely hard and we may not get it, but improving myself in the process is definitely a nice byproduct. And sometimes we don’t need the best high-tech wheel, just a simple one that is just perfect for our needs.